By Carlos Meneses

Sao Paulo (EFE).- President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva still fondly guards the almost 30,000 letters he received in prison. A “historical heritage” that, five years after his imprisonment, rests in a small computer room in Sao Paulo and shows the harsh reality of the “invisible” in Brazil.

April 7, 2018. Lula landed by helicopter on the roof of the Curitiba Federal Police Superintendence. He would not leave there until November 8, 2019, when the Supreme Court annulled the two sentences that were imposed on him for alleged corruption.

They were 580 days deprived of their liberty. The current 77-year-old president is still moved today when he remembers his time in prison. A “very hard” moment, of “resistance”, in which, in addition to physical isolation, he had to deal with the death of his older brother and his grandson.

“How many times did I lie in bed, belly up, looking at the ceiling…”, recounted the head of state with a broken voice in a recent interview.

His imprisonment shocked his followers inside and outside Brazil, who, in an unprecedented campaign, began to send thousands of letters of support to their leader at 210 Professor Sandália Monzón Street, where he was being held.

Stories of the real Brazil

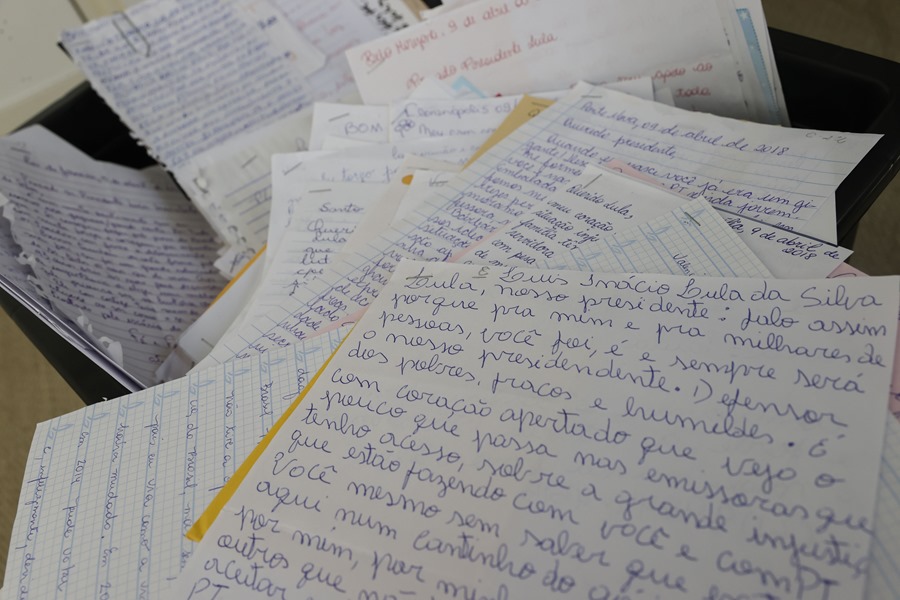

Those close to 30,000 letters are now safely stored in a room with computers at the Lula Institute in Sao Paulo. They are separated by dates and groups of origin in more than 60 colored boxes that cover an entire wall. It is known as the “Room of Letters”.

The vast majority is handwritten. Her lines contain humble stories of life, of overcoming, of gratitude. Naked stories, a faithful portrait of the unequal, poor Brazil that Lula fought in her first two terms (2003-2010) and she intends to do it again in this third.

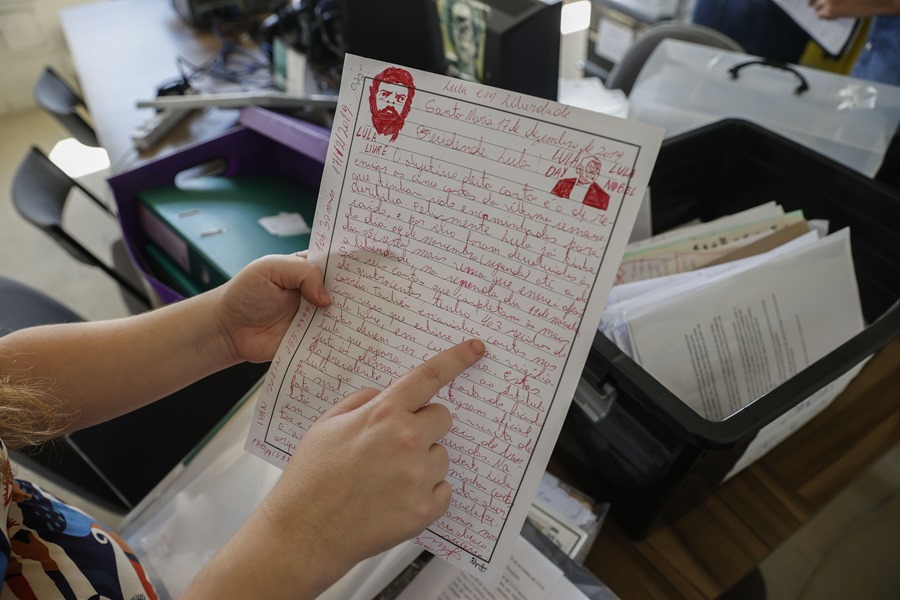

Many begin with a “Dear President Lula”, they also call him “comrade”. There are others signed with the fingerprints of illiterate people who dictated their words to a third party, as was the case of some rural workers from the municipality of Palmópolis.

“I am writing to you because I want you to get out of there soon”, begins Maria José da Conceiçao. From Fortaleza, Maria Honorio, 81, sent her solidarity message along with a small rosary attached tightly to her handwriting with five pieces of tape.

There are also true personal vents that describe the impact that the social programs that he promoted while he was in the Presidency had on their lives.

“Every day I was a crybaby. Even today I am moved by some of them”, confesses to EFE Calinka Lacort, a worker at the Lula Institute.

Letters as an act of protest

Lacort is the great guardian of the letters, which came from “almost all parts of the world”, from Argentina to Japan, passing through France, Cuba or Spain.

They arrived at the police headquarters where the former trade unionist was imprisoned and from there, given the avalanche of shipments, they were sent to the Lula Institute, where they created a permanent team dedicated exclusively to organizing this sea of epistles.

“People began to perceive that it was a way to show him that he was not alone. The letters became a political act. There were people who even sent an empty envelope” as a protest, says Lacort.

She and her colleagues took it upon themselves to read all of them, select some to send them to Lula in prison, and answer a good part of them. The leader of the Workers’ Party (PT) was interested above all in those that talked about education, another of her great obsessions.

“We would send him those batches and he would return them to us. He was curious because in some he made notes. In many he noted ‘respond’ ”, narrates Lacort.

As a curiosity, the great concerns of the Lullistas were “if they slept well, if they fed themselves and if they had blankets to sleep on,” Bárbara de Paula, a computer scientist and who later helped to digitize the letters, told EFE, a job that began after the coming to power of the far-right Jair Bolsonaro, in 2019, for fear that there would be apprehensions at the headquarters of the Institute.

Some were published in the book “Dear Lula: letters to a president in prison” (Boitempo, 2022), organized by the French historian Maud Chirio, and even the wealth of stories described in those thousands of sheets have also served as the object of study for researchers from Brazil and Spain.

Lacort comments that even today letters continue to arrive at the Institute, although now they recommend sending them directly to the Planalto presidential palace in Brasilia, where Lula returned on January 1 after a whole process of political resurrection.